|

Margate Crime and Margate Punishment

Anthony Lee

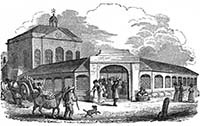

7. The Margate Lock-up.

Prisoners awaiting examination before the Magistrates at Margate or those already committed and awaiting transport to Dover gaol for trial at the General Sessions needed to be held in Margate for up to a few days. Many towns had a lock-up in which such prisoners could be held; Birchington, for example, had a simple brick structure built in 1787 ‘at the end of the poor houses to confine ill-behaved riotous persons’.1 It is not clear when such a lock-up was built in Margate. John Lewis in his History of the Isle of Thanet published in 1723 refers to ‘two watch-houses, and a watch-bell hung on the cage . . . and another watch-house built in the Fort’ and although ‘cage’ was commonly used as another word for ‘lock-up’, it is not clear if that is what was meant here.2

The first unambiguous reference to a cage or lock-up is in an anonymous booklet, The New Margate and Ramsgate Guide in letters to a friend: ‘the marketplace forms a square near the Parade, with a separate building on one side of it, which is called the Fish-market: near this is the Town hall, under which is a cage to immure offenders against the law, during, the pleasure of the magistrate’.3 Unfortunately the booklet is undated, and although the British Library suggest a date for publication of ca 1780, Gritten4 suggests the slightly later date of ca 1789; internal references in the guide, (for example ‘the town is now lighted’) are consistent with the date of ca 1789, and suggest that the first ‘proper’ lock-up was provided by the Improvement Commissioners as part of the creation of a Town Hall in the Market Place.

Permission to hold a Market in Margate was first awarded in 1777:5

Yesterday a Patent passed the Great Seal, directed to Francis COBB and John BAKER, the present Wardens of the Pier of Margate, in the county of Kent, and their successors, to empower them to open a Market, to be held on Wednesday and Saturday in every week, at a certain Market-place, now erecting upon Pier-green, in the centre of the town of Margate, for the selling of Corn, Grain, and Flour, and Flesh, Fish, Poultry, Butter, Eggs, Fruit, Vegetables, and other Provisions, together with a Court of Pie Powder.

Pier-green, previously known as the Bowling Green, was an open space where Market Place now is, and a Court of Pie Powder was a special court that had exclusive jurisdiction over disputes between merchants and consumers and any other dispute arising as a result of a market or fair.

One of the first acts of the Margate Improvement Commission established in 1787 was ‘to consider of a proper place for the erection of a building as a Room or Rooms for the future meeting of the Commissioners’.6 In June, the Commissioners reported that they ‘have taken a view of a building in the Market Place belonging to the Pier and lately in the occupation of Mr Robert Shelton Covell, which building the said Committee are of opinion may be fitted up and made convenient for the future meetings of the Commissioners and for the transaction of such other public business of the town therein as the Commissioners for the time being shall approve of, at a less expense than the erection of a new building.’ They agreed ‘That the said building be put into a proper state for the purposes intended under the directions of the Committee appointed at the former meeting’6 While the work was being done the Commissioners met in a variety of locations, including the Fountain Inn, the New Inn, the Bull’s Head, and the Vestry Room at St John’s Church, but in December 1787 they were able to meet in the New Town Room, which, by June 1788 was being referred to as ‘the New Town Hall’. 6 The early minutes of the Improvement Commissioners contain no specific reference to a lock-up but the extract from The New Guide to Margate and Ramsgate in letters to a friend already quoted make it clear that the lock-up was built as part of the conversion of the old building in the Market Place into the new Town Hall. The location of the lock-up is confirmed in newspaper reports of the time, such as the following:7

Margate Sept. 28 [1802]: A serious alarm was excited this morning by one of the stacks of hay, in Church Field, being discovered on fire. The flames were not got under without great difficulty, but happily the conflagration did not extend to the other stacks, for, had that been the case, all the extensive stabling of Messrs Bloxham would have been endangered. — On inquiry, it was wilfully set on fire by two very young incendiaries, both under 12 years of age. — They are in custody, and now confined in the cage opposite the Market place.

By 1819 the Market building was in a ‘very defective’ state.8 A Committee of the Commissioners reported:8

Having inspected the buildings of the Market, we find them in a very dilapidated state and do not think any repairs will fully answer the purpose. We would therefore recommend a new erection of them, on an improved plan, especially when we consider the peculiar situation of the town as a public resort, and the accommodation so justly due to the visitors from the great benefit the inhabitants generally derive from them.

Francis Cobb, Edward Boys, John Cramp, 6th January 1819

The Committee was then, however, asked to report ‘as to the finances of the Commissioners and how far their means are adequate to the building a new Market.’ In February, it was decided that ‘the Commissioners cannot afford to go beyond the sum of £2000, in the building a New Market’ and an advertisement was placed in the Kentish Gazette for plans and estimates for a new market, it being stressed that ‘the Commissioners will adopt such plan as includes the greatest advantages at the least expense’.8

Plans were received from two Margate builders, Charles Boncey and Richard Jenkins, and from Thomas Edmunds a surveyor and keeper of the White Hart Hotel, but, rather than choosing between these plans, it was decided to change the remit to include the conversion of four shops ‘adjoining the Market’ into houses, and so the plans were returned for modification. 8 It was also agreed that a decision should be delayed because there was now not enough time to complete the work before the start of the new holiday season. 8 When the Committee came to discuss the plans again in November, they reported that the plan of Thomas Edmunds was the most expensive and that of Richard Jenkins the least expensive, but the Committee concluded that ‘there is still room for improvement’ and it was decided that they should advertise for further plans. 8

A lack of finances continued to be a problem and in December an application was made to the Treasury for a loan of £2000, with the Town and Market rates and tolls as security. 8 In January 1820 they heard from the Treasury that their application had been refused; the Commissioners then decided to hold a public meeting in the Town Hall to discuss the possibility of raising the money by a subscription, again to be secured by the rates and tolls, paying interest on the sums subscribed at 5 per cent, equal to the Bank Rate at the time. 8

By the following week the whole of the £2,000 had been subscribed, as follows:8

| Name | Subscribed (£) | Name | Subscribed (£) |

| Ann Turner Brown | 50 | William Ladd | 100 |

| Henry Brasher | 50 | Thomas Newby | 50 |

| Isaac Barber | 50 | George Offman | 100 |

| Cobb & Son | 200 | Latham Osborn | 50 |

| Thomas Chapman | 50 | James Pickering | 100 |

| Thomas Carthew | 50 | William Paine | 50 |

| Robert Crofts | 50 | John Robason | 100 |

| Richard Dendy Crofts | 50 | Robert Salter | 50 |

| Garton Crow | 50 | George Staner | 50 |

| Edward Dering | 50 | John Sackett | 50 |

| James Denne | 50 | Thomas Smith | 50 |

| John Finn | 50 | John Swinford | 50 |

| Ralph Heath | 200 | James Wright | 50 |

| Moses Harrison | 100 | Edward White jun. | 50 |

| Daniel Jarvis | 50 |

Despite now having all the finances in place, the Commissioners again decided to delay making a decision, because they now thought that, as well as building a new Market, it might be ‘advantageous to the interests of the town’ also to rebuild the present Town Hall. 8 This was not something that the Commissioners could decide on their own, because when the Margate Pier and Harbour Company was formed it was agreed that the Company would share a joint interest in the Town Hall with the Commissioners; the Company would therefore have to be asked for their agreement. A few days later the Directors of the Margate Pier and Harbour Company, many of whom were, of course, also Commissioners, agreed ‘without hesitation . . . to the wishes of the Commissioners of the Pavement as to the taking down the present Town hall and rebuilding the same considering that such measure will essentially contribute to the advantage of the Commissioners, the Directors and the Town in general’. 8 The plan was also discussed at a Vestry meeting at St. John’s when it was agreed by ‘a very large majority, that this vestry cordially agree with the Commissioners the propriety of taking down and rebuilding the present Town Hall convinced that it will be advantageous to the interests of the town and that the Commissioners will as far as may combine economy with improvement’. 8

At the end of February the Committee considering the New Market and Town Hall (Daniel Jarvis, W. Frederick Baylay, John Boys and Edward Dering) made their report.8

The Committee having inspected the several plans of Messrs Boncey, Edmunds, Marshall and White, are of opinion that neither of them would fully answer the purposes intended, that the Committee unanimously prefer the Market Part of Mr White’s plan, but object to his plan for the Town Hall — Nor do the Committee approve of either of the plans for a Hall, but submit to the Consideration of the Commissioners the advantage which would arise from erecting a New Room immediately in front and connected with the present Building.

The idea of a ‘New Room’ to be built in front of the old Town Hall was adopted. The new Room was to be ‘45 [feet] in length, 30 feet in width and 20 feet in height in the clear, of which 4 feet be coved and that it be supported by pillars.’ It was decided that Edward White jun. and Thomas Edmunds would be asked to submit plans and estimates ‘for the proposed New Building and the consequent alterations which may be necessary in the Old Building . . . such estimate to include the building of the New Market it being understood that no part of the materials of the present Market, except those of the Fish Market be used in the New Building.’ The Commissioners specified that ‘the building of the New Market be completed by July 1st next, and the New Room by the Sept 1st next,’ a very tight deadline, which was, of course, not met. It was also decided that ‘the materials of the Market Place and the houses adjoining be put up to public sale within 7 days from this time to be cleared away within 10 days after the sale.’

By early March six tenders had been received, and that of Edward White jun, for £2539, was accepted, this being the lowest tender; Thomas Edmunds was appointed as Surveyor to superintend the work.8 The Directors of the Margate Pier and Harbour Company reported that they wished to be able to use the new Room for their meetings and so, in exchange for joint rights with the Commissioners over the building, they agreed to contribute £400 towards the cost of erecting the new Room, together with an annual rent of £5 for sixty years and an agreement to pay half the expenses of any necessary repairs.8 In April 1821 Edward White reported that the work on the Market and New Room was completed.8 In October, Thomas Edmunds submitted his account for superintending the work, which, he said, had taken fifteen months. He asked for payment at the rate of 3½ per cent, which on a sum expended of £3402, amounted to £119, which was accepted by the Commissioners.8

The new building, as well as the meeting room supported on columns with an open space below, sported a clock dial in a pediment and a bell-turret on the top.9 The old building, referred to as the small Hall, came to be used ‘as a retiring room by the [Cinque Port] Magistrates, for the Saving’s Bank, &c., and also the Police Station and temporary cells for prisoners, below’.10

It was reported to the Home Office that the lock-up had been repaired in 1821, presumably as part of the rebuilding work on the Town Hall,11 although some repair work would also have been necessary following an escape by Henry Spicer. Spicer had been ‘taken into custody for violently assaulting different persons in the street, and lodged in the cage’, following the arrest of a number of smugglers at Broadstairs.12 During the night ‘he effected his escape by the assistance of some other persons, by making a large hole in the wall, which was evidently begun on the outside.’ Although the lock-up was the property of the Margate Commissioners and the costs of construction were paid for from the paving and lighting rates, it was used by the rest of the Thanet Division of Dover.11 This led to many arguments about who was responsible for improvements to the lock-up, but on this occasion ‘after some delay and demure’ the Clerk of the Peace for Dover agreed to pay £54 12s 4d for the repairs. A plan of the lock-up dated 1820 shows two cages, one for men, one for women, with a single water closet serving both cages.13

|

Figure 5. A Plan of the Margate Lock-up, 1820. |

The state of the lock-up, even after the repairs, was very unsatisfactory and in 1825 a second local Act for the improvement of Margate included, amongst a long list of other planned improvements, a proposal to enlarge the Market Place, and a clause stating that the Commissioners were ‘authorised and required to make such alterations to the Prison under the . . . Town Hall as shall render the same more cleanly and beneficial to the health of the prisoners from time to time temporarily confined there, and so as to render the same secure against escape, and also to divide or enlarge the same in such manner that male and female or other prisoners may (when expedient) be kept separate from each other…’14 The costs of these improvements, not exceeding three hundred pounds, were to be paid by the Commissioners.

Of the £300 due to have been spent on the lock-up, the Commissioners actually spent no more than £50 ‘in improving and enlarging the Lock-up House’.11 The Commissioners argued that, despite the requirements of the Act, it would be unfair for them to pay for the work from the paving and lighting rates since this was collected only from the town of Margate, and not from those parts of the parish of St. John’s not included in the town and not from the other parts of the Thanet Division of Dover, such as Birchington and Broadstairs, who also used the lock-up. The Commissioners believed that the improvements should be paid for by Dover out of the Liberty Rate collected from the Thanet Division, but Dover argued that the lock-up belonged to the Margate Commissioners and they should pay.11 The consequence of this disagreement was that little or nothing was done to improve the lock-up and the lock-up remained as bad as ever. In 1836 John Boys, as Clerk to the Justices at Margate, had to produce a report on the lock-up for a Parliamentary investigation into ‘Places of confinement for persons apprehended for felony in Market Towns not Corporate in England’.15 He reported that ‘we have what is called the "cage;" it is on the ground-floor, beneath the town-hall in the market-place; [it] contains two strong rooms close to each other, but separated by a wall and iron gratings: the two together are capable of holding about six or eight persons; it is only used as a lock-up house for a night or two, whilst prisoners are under examination and before committal; and it has hitherto been found sufficient for all general purposes, because the Cinque Ports justices, who are resident (and three of whom are also county magistrates) have always made it a point to proceed as expeditiously as possible to investigate the charges against prisoners; and in cases of committal to commit to Dover gaol, or (in cases of great magnitude) to the county gaol. In about five cases out of six the committal is to Dover, and, speaking from my recollection and experience of 25 years, I should think the average of committals has been about 25 in the year, a great majority of offenders being only beggars, and petty offenders against penal statutes.’ He reported that there had only been one case of a prisoner escaping from the lock-up, the case already referred to above, after which the lock-up had been ‘materially strengthened,’ and that when any offender was confined ‘upon a heavy charge’, one or two constables stayed the night in the lock-up.

As well as the lock-up at Margate there was also a small lock-up at Birchington. This was just a single room ‘detached from all other buildings’, ‘but is scarcely used for any other purpose than to lock up a drunken man till he is sober, and that very rarely.’15 The lock-up at Broadstairs was similar to that at Birchington and ‘no offender of importance is ever detained in either of those places, but they are always brought immediately before the justices at Margate.’ Boys also reported that Margate could not afford its own full-scale gaol: ‘if the inhabitants of Margate were to build a gaol of their own, it is computed that they could not build a sufficient one for less than £5,000, and the debts secured upon the town-rates and pier already amount to upwards of £77,000; in consequence of which the town, is so overburthened with rates, and there is so much difficulty in collecting them, that 71 persons were in the last week excused by the magistrates on the ground of poverty’.15

Boys added a final plea to his letter to the Parliamentary Commission, pointing out how the Justices at Dover could better serve the town of Margate: ‘I venture to add one remark connected with the foregoing subject. The justices of Dover formerly held a sessions and gaol delivery at Margate as well as in Dover, and they still have power to do so; if this arrangement were tobe made, the present Margate cage might be rendered, at a comparatively small expense to the inhabitants, a place of detention for prisoners until trial, and the new Dover gaol might continue (as at present) the district gaol for punishment of convicted offenders, without any alteration of the law, or any new burthen being imposed on the inhabitants of this jurisdiction’. 15

In another report on the lock-up sent by John Boys to the Home Office, this time in 1844, he was again highly critical:11 ‘There are only two dark cells at present of about six feet square with a place of easement in each, and about a month since there were at one time five persons confined on preliminary charges, including two women.’ He estimated that about 150 persons a year were held temporarily in the lock-up. Conditions were thought to be so bad that an Inspector of Prisons was sent in 1845 to report on the lock-up:11

The Lock Up House is situated under the Town Hall and consists of only two cells, each about 6 ft 9 in by 5 ft 9 in and 8 ft 6 in high. There is a privy in each cell, and they are very foul and offensive. The cells are ventilated by gratings which open into the public street, by means of which prisoners can communicate with, and receive prohibited articles from, persons in the streets. There are open grated doors to these cells which are opposite to each other at a distance of only 2 ft 6 in, so that prisoners confined in the adjacent cells can see, and even touch each other. A case occurred about a year ago in which a youth aged 18 was confined in one of the cells, and a girl aged 14 in the other: the youth stripped himself entirely naked and danced before the girl. The Superintendent of the Police saw this, and immediately removed the girl from the cell to the Police Room. No bedding, nor even straw or a rug, is provided for the prisoners. The cells are extremely cold in winter, so much so that the Superintendent of Police states that he has frequently found the prisoners in a half perished state, and has been obliged to remove them to the fire in the Police Room to bring them to. In summer the cells are very close, and instances have occurred in which prisoners have been removed from the cells in a fainting state from their unwholesome and oppressive condition. The flooring of the cells is rotten and dilapidated so that it cannot be properly cleaned — as many as 14 prisoners have been in confinement at one time in these cells for the night and there are frequently from 4 to 5, and prisoners have been kept here as long as four days and nights together.In serious cases when prisoners are remanded they are obliged to be sent to Dover, and brought back again, a distance altogether of 44 miles, as these cells are considered so utterly unfit and insecure.

A case reported in the Kent Herald confirmed the terrible state of the cells:16

The danger and inconvenience of incarcerating persons in the station-house of this town has become a matter of serious consideration with the authorities, and some steps must shortly be taken to remedy the existing evil of risking the health and lives of persons unfortunately confined from a Saturday afternoon till Monday. The truth of the above was strongly exemplified in the case of Jane Ann Gill, who was placed in the lock-up on Saturday, the 16th instant; she had not been there many hours before the stench, arising from the drain and cesspool, had such an effect upon her system that medical aid was obliged to be called in at twelve o'clock at night, and Mr G. Y. Hunter, surgeon, remained with the unfortunate prisoner one hour endeavouring to place her in such a state of health that no further danger might be apprehended, leaving a certificate with the inspector of the total unfitness of the place to confine any person in. This state of things would not have lasted until now could the question be settled who are the proper parties to make the alteration. The commissioners of the town refuse because, it being a borough prison, the borough of Dover should do it ; — they, the corporation or borough of Dover, refuse because it is under the jurisdiction of the commissioners of the town. An inspector of prisons was sent a short time back from the Secretary of State to view the place, whose report was exactly in accordance with the opinion expressed by Mr Hunter, and still nothing had been done. J. Boys, esq., one of the magistrates, feels so strongly the hardship of confining prisoners during a remand, that the worthy gentleman, from a sense of humanity, invariably orders their removal to Dover, which is attended with a great expense.

The following week, the Kent Herald published a clarification:17

In our remarks on the inconvenience of the station house of this town, we inadvertently were led into an error in stating that the commissioners of the town "refused to make the alterations;" such is not exactly the case, although it amounts to the same. The commissioners are ready and willing to expend £200 on a bona fideand approved alteration, if the same be sanctioned by all the authorities concerned; while that sanction is wanting the cells remain in their present filthy and dangerous state.

All agreed that the lock-up was in a ‘very disgraceful condition’.11 Indeed, John Boys, rather than use the lock up, ‘invariably sends prisoners to Dover, even on remand, which entails a considerable expense upon the town’.18 As a way of breaking the deadlock over payment for the necessary improvements, the government Inspector of Prisons suggested that half the cost should be paid for by the Margate Commissioners and half from the Dover Liberty Rate. This proposal was put to the Clerk of the Peace at Dover for discussion at the Dover Quarter Sessions, but the Dover Recorder, Bodkin reported that whilst the Dover Justices agreed that the lock-up was in ‘a most disgraceful state’ he ‘now [being] called upon to make an order by which a considerable outlay will be occasioned . . . I am not satisfied that I have the power of doing what is required’.11 The case was then referred to the Treasury Solicitors who, whilst complaining that ‘the peculiar jurisdiction of the Cinque Ports was very complicated,’ concluded that the Court of Quarter Sessions at Dover ‘have no power to repair the Lock-up House at Margate’;19 it was concluded that Dover could do nothing about the Margate lock-up without a new Act of Parliament.20 The lock-up, as a consequence continued in a very unsatisfactory state for many more years.

The state of the lock-up was taken up again by the Kent Herald in 1847:21

The abominable stench arising from the ill-constructed imperfect drain in the lock-up house of this town demands immediate attention; within these few days past it has been a complete nuisance: its effects on the human system may be inferred from the fact, that prisoners are often times obliged to be removed into the Town-hall, and the policemen are obliged to walk the streets because they cannot stop in the place!!! These are circumstances well known to all the authorities in the town, and out of the town as far as Dover, the corporation of which is handsomely paid by the inhabitants for its care of the liberty rate. If we really are a limb of Dover, and we are made to think we are, Dover ought, in justice to the ratepayers, and from common humanity towards unfortunate prisoners, to improve or reconstruct the present police station. It is a plague spot to the town.

In 1857, with the Incorporation of Margate [see A Charter for Margate] the buildings in the Market Place became the Town Hall of the new Borough of Margate and in 1869 the Magistrates Court was installed in the newer of the two buildings. Conditions in the cells and for the accommodation of the Town Police remained poor and were criticized for many years to come by the Inspectors of Constabulary. In 1858 the Superintendent of Police produced an inventory for the Watch Committee.22 The Police Station contained: 1 desk and stool, 3 benches, 2 shovels, 1 poker, 1 pail, broom, and brush, 3 lamps (1 lamp imperfect), a stretcher and straps, a fender and doormat, 1 mop, two pairs of leg irons, 1 report book, 1 candlestick and lamp, 2 belts, keys for the Engine House and Market, and 2 wrenches. The Superintendents room contained: 2 charge books with an index, a large number of Police Gazettes, ‘imperfect’, 3 bundles of summonses, 1 bundle of warrants, 1 bundle of correspondence, 1 step ladder, 1 fender, 1 large table, 1 form, and 1 desk. Finally, in the Market were two fire ladders.

In 1861 the cells were of ‘inferior construction’ even though they now contained ‘water closets and a warming apparatus.23 The cells were still not very secure. In December 1864, Robert Vanheer, a prisoner on remand for burglary, escaped from the cells and the Watch Committee, investigating the escape, concluded ‘it does not appear to the Watch Committee on investigation that any blame is to be attached to the Police, but the Committee are of the opinion that the construction of the iron bars over the cells very much conduced to the prisoner's escape. Such fault has since been remedied by order of this Committee'.24 By 1879 not much had changed: ‘The cells are . . . badly constructed, ill-ventilated, and quite unfit places to detain prisoners in for any length of time’.25

The Inspectors of Constabulary had also been highly critical for many years of the accommodation provide for the Town Police. In 1863 the Inspector reported that ‘the police office is . . . badly situated, being placed in the passage of the cells, through which every person coming to the office must pass. I have drawn the attention of the borough authorities to the matter’.26 The borough authorities were slow to respond and in 1879 the Inspector was still complaining that ‘there is no proper police office, the present office being merely a desk placed in the passage of the cells’. It was not until 1882 that the Inspector could report on major improvements to both the cells and the office accommodation: ‘A parade-room, superintendent's office, and four cells for prisoners have been erected in the basement of the Town Hall, and supply a deficiency in police arrangements which has hitherto existed’.27 The number of cells had apparently shrunk to three, each being 12 ft by 9 ft by 11 ft, opening into a corridor belonging to the Police Station under the Town Hall. They each contained a flushing water-closet, were warmed by hot-water pipes, lighted by gas and had good ventilation, and there was a fixed bench in each cell, running along one side of cell. Each cell housed only one prisoner where they were detained for no more than six house until they were required to appear in court.28

|

Figure 6. The new Municipal Offices and overhead bridge 2006. [Max Montagut]. |

By 1894 the Inspectors were, however, reporting that ‘a new station is much required, the present one being very small and badly ventilated’.29 Finally, in 1897 work started on new Municipal Offices that were constructed on the site of the old Market, connected to the existing buildings by an overhead bridge (Figure 6); a new police station was built under the old Town Hall. The Town Hall buildings continued to serve as Police Station, Magistrate's Court and Town Hall until 1959, when a new Police Station was built on Fort Hill. The Magistrate's Court moved to new buildings in Cecil Square in 1971.

Finally, as well as the lock-up in the Market Place there was also a separate lock-up on the Pier for sailors. Very little is known about this lock-up, except for a report in 1856:30

attention has lately been directed to the miserable cage in which sailors guilty of any offence are put, before being examined by the magistrates. It is a small square building, with iron rails running round three sides of it, in the centre is a stove, and a very little one it is – the only means by which the place is warmed. It is cold from its position and rendered damp by a cistern which is at the top.

References

1. Alfred T. Walker, The Ville of Birchington, Ramsgate, 3rd edition, 1991.

2. John Lewis, The history and antiquities ecclesiastical and civil of the Ile of Tenet, in Kent, 1st edition, London, 1723.

3. The New Margate and Ramsgate Guide in letters to a friend, Letter IX, ca 1789.

4. Archibald J. Gritten, Catalogue of books, pamphlets and excerpts dealing with Margate . . . in the Local Collection of the Borough of Margate Public Library, Margate, 1934.

5. Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, May 28 1777.

6. Edward White, Extracts from the minutes of the Margate Commissioners, Book 1, 6 June 1787 to 12 November 1788, Manuscript, Margate Library.

7. Morning Post and Gazetteer, October 1 1802.

8 Edward White, Extracts from the minutes of the Margate Commissioners, Book 6, 10 January 1816 to 23 January 1833, Manuscript, Margate Library.

9. W.C. Oulton, Picture of Margate and its vicinity, Baldwin, Cradock and Joy, London, 1820.

10. New Margate, Ramsgate and Broadstairs Guide, W C. Brasier, ca 1850.

11. National Archives TS 25/192, Lock-up House, Margate.

12. Kentish Gazette, July 25 1820.

13. Kent Archives, U1453/P43. Plans of the Market Place.

14. An act to amend and render more effectual several acts relative to the paving, lighting, watching, and improving the town of Margate in the Parish of Saint John the Baptist in the County of Kent; for erecting certain defences against the sea for the protection of the said town; and for making further improvements in and about the said town and parish, Geo IV c 28 1825.

15. Parliamentary Papers,Return of Places of Confinement for Persons apprehended for Felony in Market Towns not Corporate in England, 1836.

16. Kent Herald, August 28 1845.

17. Kent Herald, September 4 1845.

18. Canterbury Journal, August 30 1845.

19. National Archives, TS 25/277, Margate Lockup, 20 Nov 1846.

20. Dover Telegraph, March 24, 1849.

21. Kent Herald, October 14 1847.

22. Kent Archives, Borough of Margate Watch Committee Minutes, 1857.

23. Parliamentary Papers, Reports of Inspectors of Constabulary to Secretary of State, 1860-61, 1862.

24. Mick Twyman and Alf Beeching, A Policeman’s lot, Bygone Margate Vol. 10 Nos 1-5, 2007.

25. Parliamentary Papers, Reports of Inspectors of Constabulary to Secretary of State, 1878-79, 1880.

26. Parliamentary Papers, Reports of Inspectors of Constabulary to Secretary of State, 1862-63, 1864.

27. Parliamentary Papers, Reports of Inspectors of Constabulary to Secretary of State, 1881-82, 1883.

28. Parliamentary Papers, Report of Committee on Accommodation for Prisoners in Police Courts of Metropolis and Buildings in England and Wales in Courts of Summary Jurisdiction, 1888

29. Parliamentary Papers, Reports of Inspectors of Constabulary to Secretary of State, 1893-94, 1895.

30. Kentish Observer, February 14 1856.

![The Market Place and Town Hall, [ca 1860] | Margate History](Crime Pictures/Market-thumb.jpg)